The US and South Korea have secured a landmark deal to counter the North Korean nuclear threat.

Washington has agreed to periodically deploy US nuclear-armed submarines to South Korea and involve Seoul in its nuclear planning operations.

In return, South Korea has agreed to not develop its own nuclear weapons.

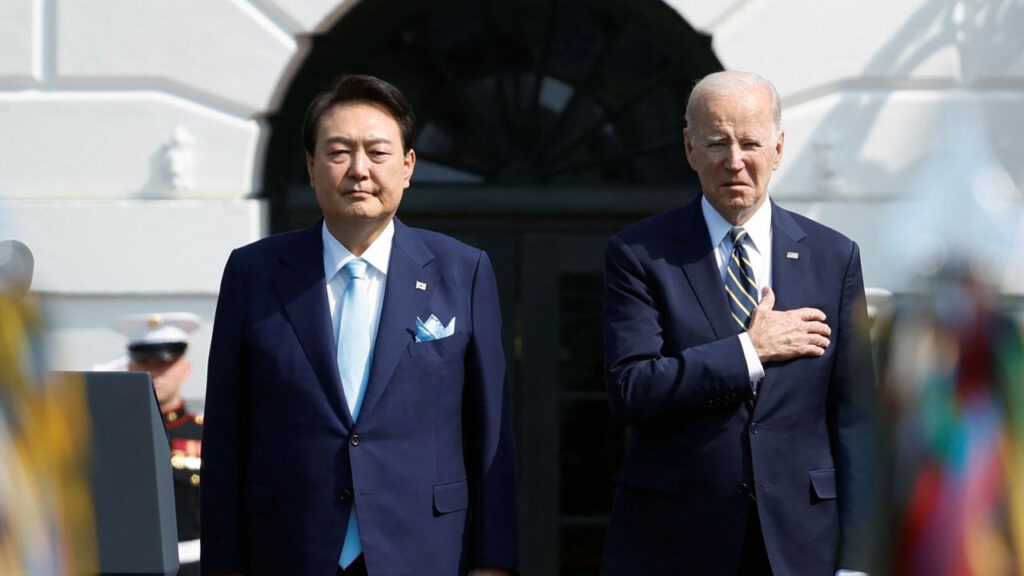

The Washington Declaration will strengthen the allies’ co-operation in deterring a North Korean attack, US President Joe Biden said.

Concern has been rising on both sides about the nuclear threat posed by North Korea. Pyongyang is developing tactical nuclear weapons that can target South Korea, and refining its long-range weapons that can reach the US mainland.

The US already has a treaty obligation to defend South Korea, and has previously pledged to use nuclear weapons if necessary. But some in South Korea have started to doubt that commitment and call for the country to pursue its own nuclear programme.

The South Korean President, Yoon Suk-yeol, who was at the White House for a state visit, said the Washington Declaration marked an “unprecedented” commitment by the US to enhance defence, deter attacks and protect US allies by using nuclear weapons.

China – clearly not pleased with the US stance – warned against “deliberately stirring up tensions, provoking confrontation and playing up threats”.

The new agreement is a result of negotiations that took place over the course of several months, according to a senior administration official.

Under the new deal, the US will make its defence commitments more visible by sending a nuclear-armed submarine to South Korea for the first time in 40 years, along with other strategic assets, including nuclear-capable bombers.

The two sides will also develop a Nuclear Consultative Group to discuss nuclear planning issues.

Politicians in Seoul have long been pushing Washington to involve them more in planning for how and when to use nuclear weapons against North Korea.

As North Korea’s nuclear arsenal has grown in size and sophistication, South Koreans have grown wary of being kept in the dark over what would trigger Mr Biden to push the nuclear button on their behalf.

A fear that Washington might abandon Seoul has led to calls for South Korea to develop its own nuclear weapons.

But in January, Mr Yoon alarmed policymakers in Washington when he became the first South Korean president to put this idea back on the table in decades.

It suddenly became clear to the US that reassuring words and gestures would no longer work and if it was to dissuade South Korea from wanting to build its own bombs, it would have to offer something concrete.

Furthermore, Mr Yoon had made it clear that he expected to return home having made “tangible” progress.

Duyeon Kim, from the Centre for a New American Security, said it was a “big win” for South Korea to be involved in nuclear planning.

“Until now, tabletop exercises would end before Washington’s decision to use nuclear weapons,” said Ms Kim.

“The US had considered such information to be too classified to share, but it is important to practice and train for this scenario given the types of nuclear weapons North Korea is producing.”

This new Nuclear Consultative Group ticks the box, providing the increased involvement the South Korean government has been asking for. But the bigger question is whether it will quell the public’s anxieties.

It does not ink a total commitment from the US that it would use nuclear weapons to defend South Korea if North Korea were to attack.

However, on Wednesday Mr Biden said: “A nuclear attack by North Korea against the United States or its allies and partners is unacceptable and will result in the end of whatever regime were to take such an action.”

In return, the US has demanded that South Korea remain a non-nuclear state and a faithful advocate of the non-proliferation of nuclear weapons. The US sees dissuading South Korea from going nuclear as essential, fearful that if it fails, other countries may follow in its footsteps.

But these US commitments are unlikely to fully satisfy the influential, and increasingly vocal, group of academics, scientists and members of South Korea’s ruling party who have been pushing for Seoul to arm itself.

Dr Cheong Seong-chang, a leading proponent of South Korea going nuclear, said that while the declaration had many positive aspects, it was “extremely regrettable that South Korea had openly given up its right to withdraw from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty [NPT]”, adding that this had “further strengthened our nuclear shackles”.

President Biden said the US was continuing efforts to get North Korea back to the negotiating table. Washington says Pyongyang has ignored numerous requests to talk without preconditions.

The US hopes to convince North Korea to give up its nuclear weapons, but last year the North Korean leader Kim Jong Un declared the country’s nuclear status “irreversible”.

Some experts say it now makes more sense to discuss arms control rather than denuclearisation.

Source: bbc